One of my favorite STEM programs combines the awe factor of potentially living on Mars and the positive impact of Citizen Science. This “Life on Mars” program was presented to youth in grades 3-5 at Skokie Public Library and would work well through grade 6.

Citizen Science, where the general public contributes to science research, is resurfacing with the help of online platforms–like Zooniverse–that curate various Citizen Science projects to support research in areas like space, climate, social science, and art. Emphasize the importance of Citizen Science to youth in the library: when non-scientists are doing scientific work for the betterment of the world, the results are powerful. We know kids are curious and learn best when their curiosity is supported. Citizen Science helps to spark curiosity with built-in follow-through.

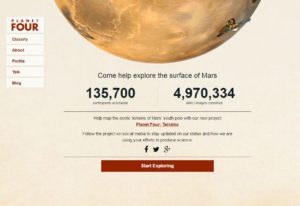

For this introductory Citizen Science program, I chose to focus on Planet Four, a Zooniverse project that classifies surface images of Mars to help planetary scientists better understand the planet’s climate. I included an introduction to Citizen Science, sharing 3-4 different examples, to lay a foundation of learning for the program before moving on to two demonstrations and then the actual Citizen Science work.

Here’s how the one-hour program was outlined.

I began with an introduction to Citizen Science (CS), asking participants if they had ever heard of the term and/or if they understand what CS was. We then collaboratively defined CS based on responses, and I continued the discussion by asking participants why they think CS is important. Responses included saving time for the real scientists and seeing things [in images] real scientists might miss.

From here I shared examples of CS projects, projecting their websites in the program room. While we navigated the sites, we discussed how these projects are being used for real science while. Examples included two local projects, Project Squirrel and Chicago Wildlife Watch. Both examine how specific wildlife inhabit the city of Chicago and surrounding suburbs, and how a change in wildlife signals larger ecological changes that could also impact humans.

Once the participants had a basic understanding of CS, I transitioned to how CS is used for space projects as well–and specifically, in the study of Mars. Once Mars was mentioned, participants were eager to share their personal knowledge of the Red Planet, guiding group conversation about what we know and why we are exploring. Participants specifically mentioned details of the recent Mars rover expeditions since this information was timely.

I focused the conversation about signs of life on planets and what we know about living things using questions and concepts from the Lunar and Planetary Institute’s Life On Mars: Searching for Life activity content. This led to our program demos:

Demo 1: Signs of Life

- To prepare for this demo, you will need two of the same style container. In one container, mix sugar and yeast into sand. In the other container, just add sand. You will also need hot water.

- Participants are presented with the two containers and are asked to make observations of the contents. Do they look/smell/feel the same or different? On the surface, both containers look the same.

- Ask what youth think will happen if water is added–then add equal amounts of hot water to each container. As water is added, ask participants again to observe any similarities or differences between the two containers. One container is bubbling and has an odor.

- Participants should discuss how they can’t see the difference between the containers until the hot water was added. This conclusion ties back to studying the surface of Mars: the surface only shares a little information about the planet.

Demo 2: A Book by Its Cover

- Choose a picture book whose cover doesn’t exactly match the story inside, like David Wiesner’s Mr. Wuffles. Show the cover to the kids.

- Ask what they think they know about the story by just looking at the cover design, including colors and font styles. For example, kids may guess that it is a funny book about a cat since there are bright colors in the background and bubble-like letters for the title.

- Explain what the story is about by talking through the book, showing a selection of full page spreads.

- Once again, what was on the surface–in this case, the cover– and what was inside didn’t totally align, just like in Demo 1.

Conclude the demos by emphasizing that studying the surface of planets like Mars or books like Mr. Wuffles gives scientists or readers hints about life or storylines, but ultimately we need to examine further to get a full understanding. CS helps scientists with the initial parts of their research, allowing more time for deeper understanding.

And now, the CS work with Planet Four can begin. I projected the homescreen of Planet Four while participants worked individually or in pairs at a tablet. As a whole group, we worked through the tutorial together to understand that we are looking for fans and blotches in the images shown on our screens. We also worked through several images as a group, allowing participants to ask and answer questions about what they were seeing. Then participants worked individually or in pairs, classifying 3-7 images each.

After about 15 minutes of work time, we had a group discussion about what we learned with Planet Four. One 4th grader commented about how much time it took to get through just one image. I related this back to scientists spending days and months and years on research, and how us spending 15 minutes is actually really helpful. We then counted the number of images everyone classified, wrote that down on a handout, and talked about how working 15 minutes a day added 12-15 images to the 4,969,810 already classified images. And if we kept working just 15 minutes a day, over 5,000 images would be classified in a year. In this case, math sold the importance of CS.

This “Life on Mars” program harnessed kids’ existing interest in Mars to introduce them to Citizen Science–and then immediately allowing them to do Citizen Science work to contribute to scientific research. I encourage you to introduce your community to Citizen Science in a program setting, too!

Leave A Comment